for diverse, democratic and accountable media

Miners' Strike - Cabinet papers expose cover-up of massive MI5 operation

blog posts |Posted by Nicholas Jones

During the 1984-5 miners’ strike so much phone-tapping was going on that the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong, took immediate steps to ensure that no mention was ever made of its extent.

During the 1984-5 miners’ strike so much phone-tapping was going on that the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong, took immediate steps to ensure that no mention was ever made of its extent.

Margaret Thatcher’s success in hushing up the bugging of phones by the Security Service MI5 is finally revealed in her 1985 cabinet papers released by the National Archives.

Action to prevent public disclosure of the role of intelligence officers was personally approved by the Prime Minister.

Government-appointed lawyers were even on the point of being advised to prepare to withdraw legal action over the hunt for NUM funds for fear of awkward questions being asked in court.

Armstrong’s intervention to ensure a cover-up over the role of the Security Service in the pit dispute was highly significant given the events that were about to unfold....

Later that same year, in a Channel 4 documentary, the former MI5 intelligence officer Cathy Massiter blew the whistle. She revealed there had been illegal bugging of the telephones of political and human rights campaigners during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Throughout the year-long pit strike Arthur Scargill and other leaders of the National Union of Mineworkers always believed their phone calls were being intercepted and their movements closely monitored.

The Cabinet papers revealed that Thatcher was warned on 1 February 1985 of the danger to her government’s reputation if it leaked out that the Security Service might have crossed the line during the strike.

She was told by the Cabinet Secretary that while intelligence gathering could be justified to counter threats of support for the strikers from foreign governments or organisations there might not be the same legal justification for the interception of telephone calls within the UK during the course of an industrial dispute.

All detail of the information gathered by interception and secret surveillance during the pit strike has been withheld from the documents released by the National Archives.

As a result there is no indication within the files as to the precise purpose of intelligence operations or the outcome of co-operation between MI5 and the Police.

Occasional brief references confirm the role of the Security Service: in November 1984 Thatcher was warned by Downing Street press secretary Bernard Ingham that he thought that nothing “further should be done covertly while the strike is collapsing”.

Among those whose movements were also being monitored was Professor Vic Allen, described in the cabinet papers as “a friend of Arthur Scargill”, who was about to fly to Moscow.

Thatcher asked the Cabinet Secretary whether Allen had “travelled under his own name” and whether Downing Street was “considering obtaining publicity for his visit”.

Much further

The 1985 cabinet papers go much further than those released for 1984 in disclosing information about one critical surveillance operation, and the details that have emerged do provide more confirmation of the role played by the Security Service in helping Thatcher defeat the NUM.

As the strike action intensified, interception of telephone communications had become so extensive that the intelligence agencies were able to identify almost instantly the individual members of staff at union headquarters in whose names NUM money had been moved out of the country for safekeeping.

Government-backed legal action to seize the £8.5 million that had been transferred to banks overseas was so successful that law officers had to advise that a case involving the sequestrators might have to be abandoned because of fears that the scale of the surveillance would be revealed in open court.

Assisted by highly-accurate intelligence about the NUM’s clandestine operation, chartered accountants Price Waterhouse managed to freeze secret accounts in Luxembourg, Zurich and Dublin without the union’s knowledge and before further withdrawals could be made.

When senior civil servants realised that evidence of widespread telephone taps had leaked out to lawyers, the Cabinet Secretary warned the Prime Minister that her government would have to be careful.

Sniffing round

The press were “already sniffing round the story” and Armstrong told Thatcher that it would “not take a Sherlock Holmes to deduce” that an unnamed official, who had been attending government briefings, was in fact an officer in the Security Service.

The revelation thirty years after the strike that it was not the banks but the intelligence services that helped Price Waterhouse track down the NUM’s assets explains how I was misled when preparing a special programme on the hunt for the miners’ money Codename Tuscany that was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in March 1986.

My investigation attempted to explain how the sequestrators had succeeded so quickly in seizing the NUM’s funds after the union refused to pay a £250,000 fine for contempt of court over the legality of the strike as a result of the union’s failure to hold a secret pit head ballot.

I was encouraged at the time to believe that it was tip-offs from bankers that led the sequestrator Brian Larkins, a partner in Price Waterhouse, to Nobis Finance in Luxembourg where £4.7 million had been deposited in the names of two members of the NUM’s staff.

Different tale

Thatcher’s cabinet papers tell a different tale: my 1986 script line about how the hunt for the money was comparable to a detective story where the reader knows “who dunnit, but not how” underlines how mistaken I was.

Even before the strike had started in March 1984 the NUM had transferred £8.5 million out the country. In the months that followed, as the strike intensified, the money was moved around, through seven countries. After passing through banks as far afield as the Isle of Man and New York, the funds finally ended up in Dublin, Luxembourg and Zurich.

“Tuscany” was Scargill’s code word for moving the money and the day before the NUM was fined for contempt of court in October 1984, two NUM officials flew from Jersey to Luxembourg carrying with them £4.7 million in dollar bearer bonds which could have been cashed anywhere in the world.

Three weeks later, without the NUM’s knowledge, Brian Larkins had traced the money to Nobis Finance. Price Waterhouse had already been given secret and unlimited indemnification by the Attorney General Sir Michael Havers to meet their expenses, an unprecedented step in such cases.

Blown cover

All that was ever said at the time in open court was that the NUM’s “cover was blown”. When I interviewed Larkins the following year, he refused to divulge his source but said that it was information from other banks that provided Price Waterhouse with “almost all, if not all the picture” of how the money had been moved around.

My suggestion that the walls of bank secrecy had somehow been breached in order to assist Thatcher is now proved to be correct, but was clearly not the full story. Unknown to me, Larkins had in fact been given a head start during his secret meetings with Robert Armstrong.

A Cabinet Office note dated January 1985 stated that “information which may be of assistance” was being passed to Price Waterhouse. Next day a note by the Deputy Treasurer Solicitor Gerald Hosker revealed that government-appointed lawyers in a case in Dublin had warned that it might be necessary to make “a tactical withdrawal” as the Irish judge was likely to probe the source of the information that was being given to the sequestrators.

Armstrong, evidently alarmed by the notification that lawyers were aware of the extent of the intelligence gathering, wrote immediately to Thatcher to warn her that the role of the Security Service had leaked out.

He explained how he had personally met Brian Larkins on “three or four occasions”; on each occasion he had been “accompanied by an unnamed man” who had passed on intelligence information.

The aim of the meetings was to have an exchange of information: Price Waterhouse perhaps had information that would assist the Security Service discover the extent of the overseas financial assistance the NUM “might be seeking or getting”. By then both Libya and the Soviet Union had been identified as possible sources of money to help the NUM fund the strike.

Armstrong told the Prime Minister in a note dated February 1985 that he had asked Larkins to keep the role of the security services “absolutely private to himself” but the need for discretion “had not been respected”.

Lawyers in the Irish courts were aware that intelligence information had been handed over, including “the names in which bank accounts to which NUM funds were being transferred might be registered” – these included the names of the two union officials, head of administration Trevor Cave and chief financial officer Stephen Hudson, who had flown to Luxembourg with the £4.7 million in dollar bonds.

Tantalising references

As government censors have succeeded in removing all but a few tantalising references to the extent of secret surveillance during the miners’ strike, the Cabinet Secretary’s note is all the more illuminating because it shows how far Thatcher was prepared to go in order to defeat the NUM, and the tension this was causing within Downing Street and the Cabinet Office.

Despite his guarded language, Armstrong does not hide his unease over the extent of intelligence gathering to speed up the legal process by assisting Price Waterhouse to seize the NUM’s funds after the union’s refusal to pay the fine for contempt of court:

“The unnamed man was an officer of the Security Service, and the information concerned was obtained in the course of the inquiries into sources and movements of NUM funds particularly overseas.

“Brian Larkins was not told who the unnamed man was or what organisation he represented or the source of the information. But it does not take a Sherlock Holmes to deduce that he was an officer of the Security Service, and that at least some of his material could have been, and probably was, obtained by interception of communications.

“I am not particularly concerned about my own name coming out in this context. I am, I suppose, under the same duty as any other person to assist the sequestrators, as the officer of the court, in carrying out the order given to him.

“I am, however, concerned about the conclusions that will be drawn about this involvement of the Security Service and about the activities in which it was engaged in connection with the NUM dispute.

“It could be argued, I think, that it was legitimate use of interception to seek to discover what assistance the NUM was receiving from overseas in the provisional movement of funds; it would be more difficult to justify the use of information obtained by interception to assist the searches of the sequestrators."

Heavily underlined

Robert Armstrong could not have been clearer in his warning to the Prime Minister: she needed to be cautious and should think through the consequences if the extent of the intelligence gathering became public knowledge. Her papers show she had heavily underlined that paragraph.

Another note to Thatcher from her principal private secretary Robin Butler reinforced Armstrong’s caution: there were some indications that “the press are already sniffing round the story” and it was likely the role of the Security Service would come out.

Both the Attorney General and the Home Secretary, Leon Brittan, had advised that the sequestrators’ case should not be withdrawn in the Irish courts; Price Waterhouse “should confirm if necessary" their contact with the Cabinet Office but insist the content of any exchange was confidential.

At a meeting in Downing Street Thatcher backed the law officers and said that if the sequestrators were questioned about their contact with the Cabinet Office, they should object on the grounds this was not relevant to the case in Dublin.

She insisted that in any case the sequestrators should give no further details of contacts with the British government “beyond saying that such contacts were for the purpose of obtaining information and did not involve taking instructions”.

Utmost importance

Armstrong told the Secretary of State for Energy Peter Walker that if the judge in Dublin or the NUM’s counsel asked about the nature of the information that had been supplied to Price Waterhouse, and if this was raised with him in the House of Commons, it was “of the utmost importance" that he was “not to go beyond" the line that the sequestrators took their instructions only from the court and not from the British government.

In the event Walker was not challenged by MPs over the speed with which Price Waterhouse had managed to seize the NUM’s funds. There were no further leaks, so even this sketchy insight into the role of intelligence gathering has remained a secret for thirty years.

However, Thatcher’s papers do contain another tantalising reference to the role of the security services. In November 1984, as the return to work was gathering pace, her legendary press secretary Bernard Ingham gave advice on how the government should handle what he feared would be a “messy" end to the strike.

The interests of law and order and democracy

The Prime Minister’s message should be that her government “only did what unfortunately it had to do...in the interests of law and order and democracy". But, in a brief sentence, Ingham did hint at the extent of the surveillance and other secret counter measures: “I do not believe anything more should be done covertly while the strike is collapsing."

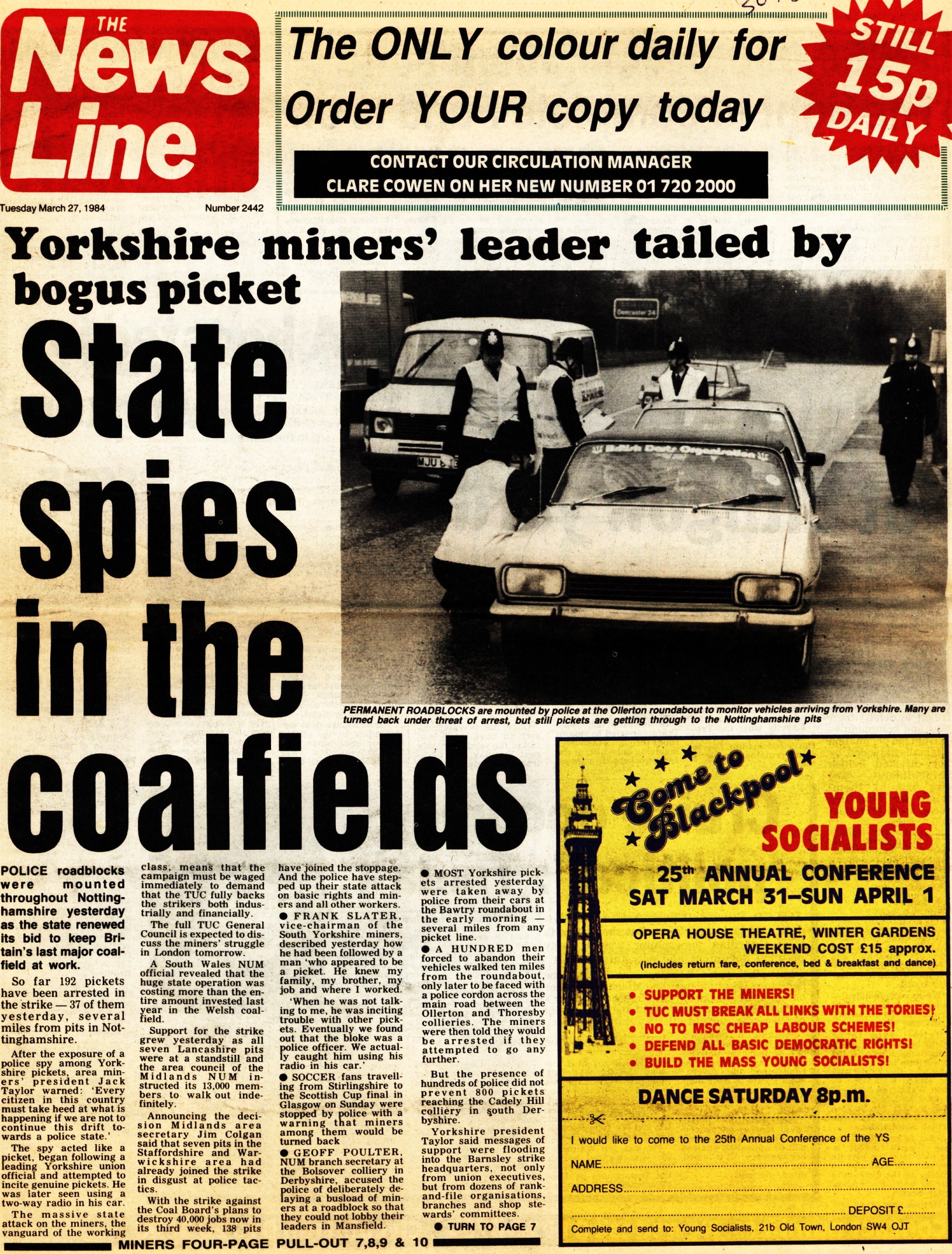

One of the significant disclosures in Thatcher’s cabinet papers for 1984 was that a week into the strike she intervened personally to tell chief constables to “stiffen their resolve” in controlling unlawful picketing. Within days the Police had introduced road blocks on motorways to stop “flying pickets” heading for working pits in Nottinghamshire and other coalfields in the Midlands.

The 1985 cabinet papers reveal that towards the end of the strike the Police were using a national computer “tabulating the conduct of trouble makers”.

Thatcher was told by her policy unit that progress had been made towards the apprehension of “conspirators behind some of the intimidation” that had taken place in the mining communities, yet another indication of how counter measures initiated during the prolonged pit dispute had facilitated steps towards national policing.

The full accounts of these and other revelations can be read at http://www.nicholasjones.org.uk

30 December 2014

DATELINE: 30 December, 2014

Share

Your comments:

Miners' Strike - Cabinet papers expose cover-up of massive MI5 operation

Yes Kieran it did - not over Wapping, when the union avoided getting into confrontation with the state by deciding, narrowly, not to order its members to strike -- but over the thorny dispute at Dimbleby Newspapers in London - in 1982, before the miners strike - when it defied a court injunction to stop a strike against the use by Dimbleby of a printing firm with whom the union was in dispute - a long and convoluted story, graphically told if you can get hold of it in the book Journalists: 200 years of the NUJ, Profile Books 2007, pages 114-119.

Posted by: Tim Gopsill: 9 Jan, 2015 00:00:00